By T.J. Masters

For the last eight years, I have produced and hosted an FM radio program on KOOP 91.7FM. Earlier this year I made the decision to retire the show at the end of the station’s yearly season cycle. And so last Thursday I aired my final episode, and this Thursday I have to find something else to do with the time between 4:30 and 6:00. Of course, it wasn’t only those 90 minutes per week that the show occupied; I realized early on in my tenure that in order to produce something compelling, I would need to try to be engaged with music—or the possibility of music (more on that later)—at all times throughout the week.

On the surface, this doesn’t seem like too much of a stretch for someone who was working full-time in live music production, who moonlights as a musician and songwriter, and who essentially lives, breathes, shits (and talks shit about) music all the time.

But becoming a radio DJ fundamentally changed my relationship to music, and instead of writing sentimentally about how it feels to end a beloved and long-running obligation, I thought I would try to describe that shift.

“How do you find music?”

The most frequent question I was asked over the last eight years vis-à-vis the show was, “how do you find the music that you play?” Whenever someone posed this question, I could tell that it was not only because they were curious about what’s under the hood; instead, it always came with a diffuse sense of yearning, as though people could sort of feel that their connection to music was not what it could be or what it once was, but that there was no clear path toward renewing that connection. Perhaps as a DJ, I had the map.

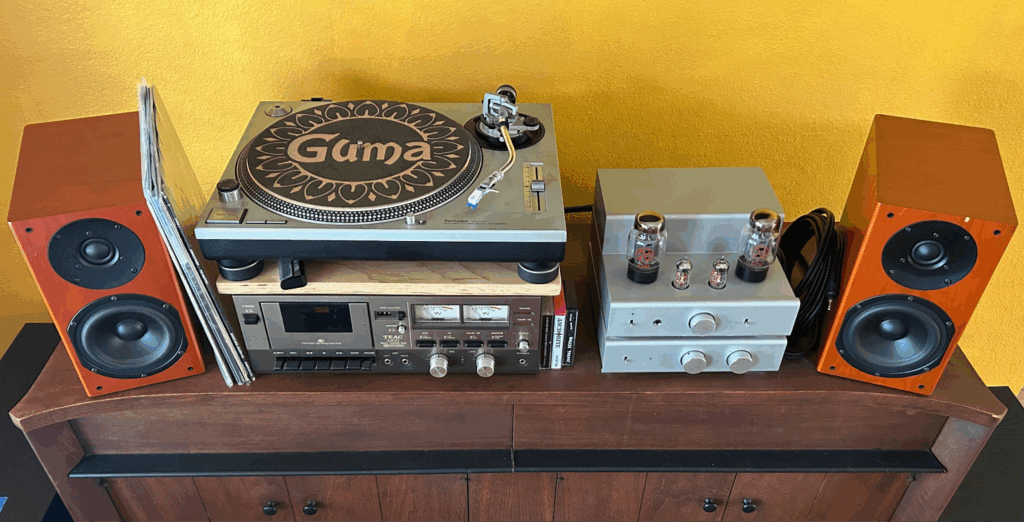

To me, this question was also weighted with a palpably deep (and possibly subconscious) dissatisfaction with how we engage with music at present. Our current fashion of listening, about which I’ve written in this newsletter, has been lassoed by a very small number of very rich people and shunted to their preferred money machines (read: platforms), paradoxically offering unprecedented access to recorded material while devaluing it in toto. In my lifetime, people have gone from having many great and wild rivers of media to explore to having one thin, black, glass rectangle through which they must attempt to access not just music but everything. Don’t get me started on the peppercorn-sized “speakers” through which we’re expected to listen or the general lack of experience with home stereo systems, which do not have to be expensive to be good.

I’ll also spare you the artist’s tired lament about this great cultural smoothing, which affects not just music but all forms of art—in part because that lament is rapidly being eclipsed by an even greater existential punishment, which is AI-generated content that in only a year or two has become largely indiscernible from “the real thing” and which, as a result, degrades the experience of all things.

An iPhone is not a stereo. A Sonos is not a stereo. A soundbar is not a stereo. If you want to not just hear music but to really listen to it, you need to get two speakers and hook them up to an amplifier. That is a stereo. Guma turntable slipmats are here.

Anyway: how do you find music? The answer is not complicated: you pay attention to it.

[pull quote] “…A pan-artistic approach that doesn’t devalue the Artist as much as it elevates everyone else on a record to the level of importance enjoyed by the person whose name is on the front.” [/pull quote]

Moreover, you pay attention to the people that made it. After less than a year of producing the show, I had combed through my entire library of heretofore collected music from the age of 12 to 28. I needed to expand rapidly, and I soon started to hit a groove where, on any given week, up to 100% of the material I was broadcasting was brand new to my ears. The show became less about my own small world and more about digging deep in the hopes of finding other ones. This imbued the show (and my hosting) with a kind of kinetic energy that fed mine and my listener’s spirits. Simply put: it’s exciting to share things you’re excited about.

Week to week I probably averaged more like 75% “new” material, and I almost always got there by following the people who made the music that I already liked. I could give you an exhausting list of web resources and tell you how to use them, but it’s really quite easy. Use the internet to look up the names of the people on your favorite record, and then go listen to the other things they made. This is a pan-artistic approach that doesn’t devalue the Artist as much as it elevates everyone else on a record to the level of importance enjoyed by the person whose name is on the front. Do you like the sound of a certain hit record? Look up the producer and/or the engineer who made it—it’s more than likely you will find that the same team of people, including some of the same musicians, worked on another record in the very same year that was consigned to the dollar bin but which has all of the sonic hallmarks of the “hit” record that you love (and maybe even a great song or two).

Do you just love the bass on Chaka Khan’s “What Cha’ Gonna Do For Me” the way I do? Lucky for you, it’s trivially easy to learn that the person who played that bass was Anthony Jackson, and according to discogs.com he has 779 other credits to his name. Here in less than one paragraph we have conjured 779 new homework assignments: all you have to do is go listen.

One of the links in that previous paragraph is to a YouTube video, and I point that out to make it clear that I’m not a complete hater of technology, algorithms, and streaming. All of those things are tools, and without them the last eight years of DJing would have been exponentially more difficult. But I do think it’s worth pointing out that an AI-generated song is a dead end in this regard. There are no people involved except the ones whose life work was massively and indiscriminately (read: unprovably) exploited to train the computer how to generate that song. Even if you did enjoy an AI-generated song, there is no replicable or reliable way to get more of that same thing. All AI generation is irreproducible, and not even the creators of the technology can trace the pathways taken by the machine to land on a certain result.

But in all of this, there is activity. If you want to find music, you have to look! Make a personal choice to reject the passive listening experience offered by algorithmically-generated playlists. Back in the day, no one would ever have gone to a Starbucks hoping by chance to catch their next favorite song farting out of the 70V ceiling speaker system. But now the majority of consumers do essentially this every day by letting Spotify choose their music. I don’t know anyone who actually likes this, especially since the AI floodgates are open and Spotify is doing nothing in the way of curatorial culling, and definitely not in light of their proven reliance on for-hire fake artists to generate soundalike material for which they owe no royalties and which they can use to stuff their playlists (Really.).

I have no space in my life for this; if I have not chosen to listen to something—even if that something is another DJ’s mix—I am listening to silence.

The Possibility of Music

When you choose to make listening an active part of your conscious experience, you become open to the possibility of music. Ironically, maybe you can catch your next favorite song on the PA at the grocery store, but more regularly what this means is that your ears (and your mind) are always open. Being aware of the sounds around you, engaging and sharing with friends, and actively researching and seeking are one thing, but it’s that second organ—the mind—that really unlocks the door.

Producing a radio show for eight years has, hands down, made me a more sympathetic, open, and confident listener and critic. Let me explain.

When you are responsible for 90 minutes of program material every week, you have no choice but to listen to music. Whether you’re digging alone or getting recommendations from a friend, you must tune your mind to the hope that whatever is in front of you could make for adequate program material. The job becomes nigh impossible if you retain any sort of prejudice or snobbery whatsoever.

Then as a DJ, your job is to serve up your discoveries on a silver platter to the listener. Your one goal, other than the discovery of music, is to do this in such a way that people keep listening. A true enthusiasm for the material absolutely must be present. The personality and presentation of the DJ is part of the artistry of broadcast; nobody says “oh I love the music on this show but I just can’t stand the DJ” or vice versa. And no DJ says, “I hated all this music when I was listening to it, so now I’m going to make you listen to it too.” When I was training volunteers in how to broadcast at KOOP, I always tried to impart this holistic, triangular idea of Music + DJ + Time being the raw materials for a broadcast. You have only these three things at your disposal, and you must spin them in such a way that your result—which is purely aural and can be experienced anywhere from a car in loud traffic to a living room to a restaurant kitchen to a bike shop—is the most compelling thing in the air.

As a musician and an artist, I found the necessity of enthusiasm to be incredibly therapeutic and helpful in my own personal growth. Artists are sensitive, sore, easily bruised. I have known many aspiring musicians who, like myself at one time, lacked enough confidence in their work to avoid being hurt by the work of others. Of course, it’s not others’ work that is hurtful, it’s your own ego. This closed-mindedness—expressed as snobbery, petulance, or some combination of the two—is only bad.

I don’t imagine that you suffer from this particular sensitivity, but when I started this program in my late 20s, it was revelatory to perform this kind of weekly “exposure therapy” on myself. I pushed myself to follow all leads, to at least check things out, and not only did I discover bottomless wells of subculture, genre, and style, I became increasingly confident in my own work and in my own taste. “It’s not for me” is anathema to the snob mentality, which craves at any cost to express a “superior” opinion. As with any expertise, the more you do it, the better you get. I found that being open-minded—initially out of desperation for program material but increasingly because it’s fun—did not dull the edge of my opinion but actually increased my capacity for criticism and discernment. I got to a point where I could tell within the first five or ten seconds of listening to a recording whether or not it would be a good fit for my show. Part of that is a preference for certain genres over others, but a large part of it too is simply self-knowledge. The more you listen, the more you discern.

Combine open-mindedness with an enthusiasm for the material, and you’re cooking.

Large Hot World

The name “Small Cool World” always reflected myriad meanings and so delighted me even if I thought I sounded corny saying it out loud. It is a small world, and we all see evidence of that in our daily lives. The “cool” part of the world is even smaller and has always been worth seeking.

I started my program the same year that Trump took the office of the President for the first time. The year Austin TX started reliably breaking summer temperature records on an annual basis. The show took a break during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now there is war in Ukraine; concentrated genocides in Gaza, Myanmar, and elsewhere that are supported by United States tax dollars; U.S. concentration camps; deportations; a cocktail of conspiracy theories and general illiteracy have split many American families in two, and others have been wholly decimated by the anti-human agendas at work. The list goes on. A lot can change in eight years, and sure you could pick any year of recorded history and spin up the atrocity exhibition, but suffice to say that it doesn’t feel like a small, cool world anymore—at least not enough for me to stake my name on it.

The show was always predicated on my mood. This was very out of step with KOOP’s style of programming at the time, wherein program applicants tended to focus on an area of expertise or specific genre(s) around which to organize a program. In my application, I essentially told our elected committee of program directors that I thought I could do a show where my personality was the only constant. They took a chance on that concept, and eight years, some 400ish shows, and 600 hours of broadcasting later, the proof of concept is complete.

How do you find music? I don’t really know, but I do what I think works. I do know that a lot of people found a lot of great music through my work, and that is satisfactory to me. One of the hardest parts about this departure is explaining to those who are kind and interested enough to ask “why” that I don’t really have a reason for stopping except that it feels like the right thing to do. I want to.

About halfway through my run, I started a Discord channel to try and encourage listeners to text-chat with me on the air. It never really took off, but after a listener told me they’d been saving my playlists, I began using it as a place to keep my own record of what I had aired. This became an essential library that I searched from week to week to help remember if I had played an artist or song before.